Towards the Abolition of Biological Race in Medicine and Public Health: Transforming Clinical Education, Research, and Practice

Section 1: Racism, not Race, Causes Health Disparities

What are racial health disparities and why do they exist?

Racial health inequities exist and persist. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, racial health disparities are the “higher burden of illness, injury, disability, or mortality experienced by one (politically and socially constructed) population group relative to another.”[1] We use racial health disparities synonymously with racial health inequities, although we acknowledge there are subtle differences and that inequities is preferred by some because it draws attention to the power imbalance at the root of the issue.[2]

In the United States, this can be seen by the disparately high rates of cardiovascular disease, renal disease, diabetes, stroke, certain cancers, low birth weight, preterm delivery, and more between people of color (often Black) and white people.[3] Biomedicine tends to interpret these disparities as evidence of fundamental genetic differences between socially constructed race categories. Yet, a growing body of evidence from medical journals emphasizes that these health disparities stem from inequalities in power and socioeconomics, not from genetics (for more on the body of evidence, see appendix 1).

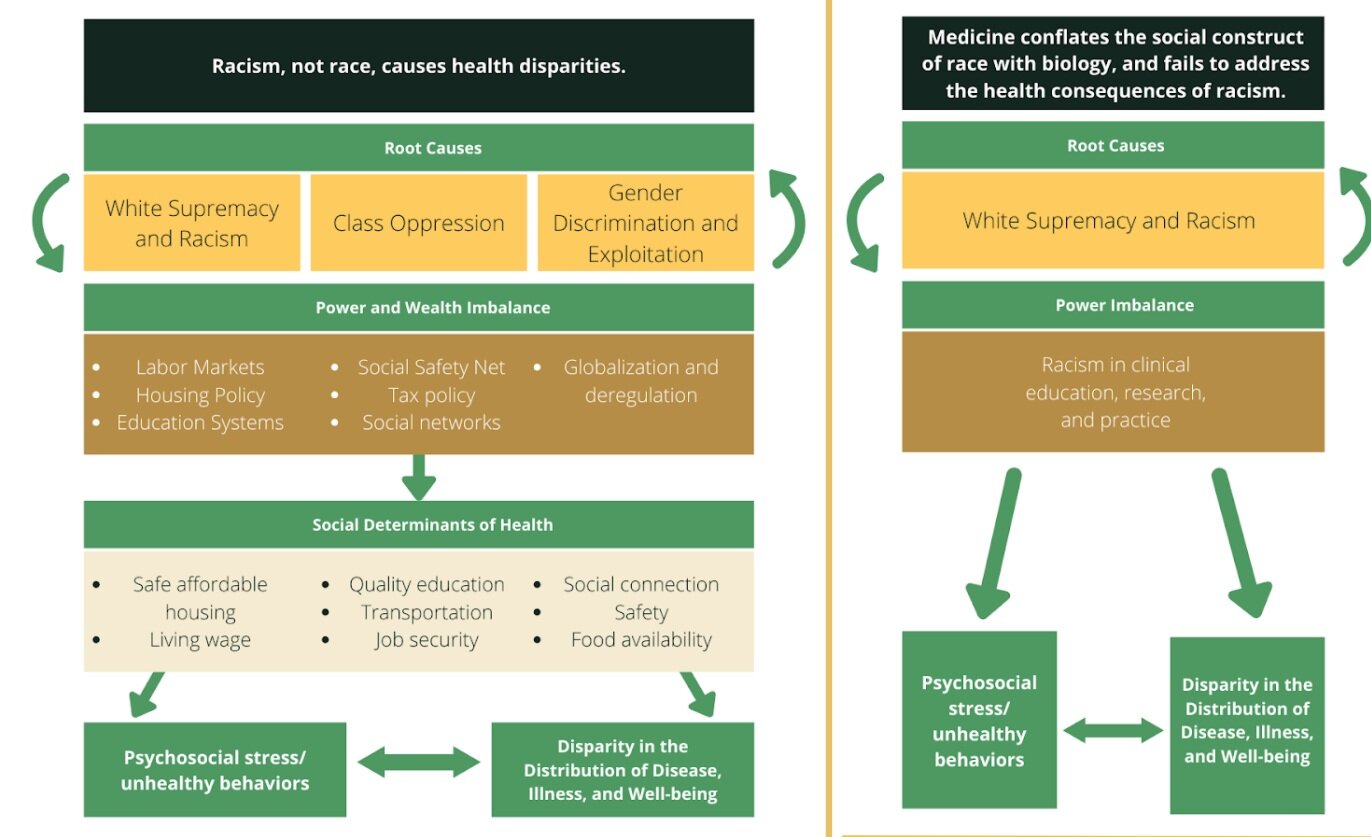

Dr. Joia Crear-Perry, a fierce physician advocate for Black maternal health equity, adapted the guiding mantra that “racism, not race, causes health disparities,” as seen in the following graphic to show the mechanisms of how racism causes health disparities.[4] We adapted her model (on the left) to show how this works in clinical education regarding the use of “race as biology” (on the right). In this section, we explain how racism causes health disparities, our model, and how we define the terms we are using. Rather than use heuristics and simplifications, it is critical that we as a medical profession address racism head on and in all its subtleties.

Source: Graphic adapted by Dr. Joia Crear-Perry, originally from Tackling Health Inequities through Public Health Practice, by R. Hofrichter and R. Bhatia

Dr. Crear-Perry shows that health disparities start with root causes (racism and white supremacy, class oppression, gender discrimination, and exploitation) to create deep power and wealth imbalances across much of the systems that govern our lives, such globalization and deregulation, labor markets, housing policy, education systems, and much more.[5] These, in turn, mold the social determinants of health by shaping who is paid how much and with what benefits or job security, who is allowed to live where, what quality of housing they can afford, what quality of education exists for them or their children, what quality of food is available, and much more. These mean that differential power distributes the social and environmental determinants of health differently, depending on who holds and doesn’t hold power. In the United States, this tends to fall primarily along race, class, and gender lines, with those who hold multiple marginalized identities, such as Black working-class women, even further marginalized. These social determinants of health lead both to an unequal distribution of disease and well-being (e.g., increased asthma rates in neighborhoods with poor quality housing and increased environmental exposures) as well as psychosocial stressors and unhealthy behaviors.

For our focus as medical students, when clinical education and medicine at large conflate the social construct of race with biology, it entrenches racism across the system. This means we as providers not only fail to address in practice how racism is creating health disparities, we also create and perpetuate racial health disparities. We define institutional and structural racism in this paper, but a system that is racist produces power imbalances along race in medicine, leading to racism in clinical education, research, and practice. We argue that this racism encourages providers and researchers to largely ignore social determinants of health, and instead focus on the most individual and most superficial aspects of health inequities—skin color as a predictor of epidemiological “risk,” individual behavior, etc.

Many health-care practitioners and researchers—even those who pursue justice and equity through their work—will ascribe observed racial health disparities to essentialized notions of biological racial difference. A recent study shows an alarming number of medical trainees wrongly believe Black people literally have thicker skin that biologically accounts for a perceived higher pain tolerance.[6] This and several other examples outlined in this paper (such as the calculations for kidney function) show how physicians conflate racial health disparities with biological difference, affecting how physicians diagnose and treat patients of color and directly causing a differential distribution of certain diseases by race. This conflation asserts a (false) naturalized racial hierarchy and perpetuates flawed science. Furthermore, it fundamentally distracts from the true ills that negatively impact people’s health outcomes and well-being: racism as a root cause of inequities in society.

Many more health-care practitioners do not question the rubrics in the differential diagnoses that assign individual “risk” for different diseases or illnesses based on only epidemiological population data or assumptions on individual behavior based on skin color or culture. These assumptions obscure the power differences that shape social determinants of health, which is why our diagram skips the social determinants entirely, because we are taught to gloss over or blatantly ignore them in our training, instead exhorting our patients to simply “eat better and walk more.”

All of these add up. This confusion and unquestioned acceptance of biologization of race in differential diagnoses and medical education has dangerous consequences: patients who are diagnosed later and with worse outcomes, given health education that doesn’t address their lived experience, and whose care directly causes psychosocial stressors based on their perceived race.

This inattention to root cause and direct creation of health inequities is our call to action. Through this paper, we hope clinicians, researchers, educators, and students will join us in our vision of a world where the social construct of race is not conflated with biology, and where the health consequences of racism are acknowledged, addressed, and cared for in all forms. To understand this graphic better, we further define racial health inequities, race, white supremacy, and the five types of racism, key terms that are the foundation of our vision.

In order to understand how medicine can become antiracist, we must first be on the same page about what racism truly is and how it harms our communities. Therefore, in order to highlight the intentionality underlying the language we use throughout the rest of our paper, we will next define key terms relating to race and racism.

A note about language

Throughout this paper, we strive to follow the example of critical race scholars and activists before us in the language we use. Critical race theory states that race is constructed by society and places the construction of race and the resulting racism at the center of any analysis. These scholars include W.E.B. Du Bois and Kimberley Crenshaw, whose work has taught us to capitalize the word “Black” when referring to Black people. Crenshaw states, “I capitalize ‘Black’ because ‘Blacks, like Asians, Latinos, and other “minorities,”’ constitute a specific cultural group and, as such, require denotation as a proper noun. By the same token, I do not capitalize ‘white,’ which is not a proper noun, since whites do not constitute a specific cultural group.”[1] Although we acknowledge that the concept of “white” as a cultural group has been since questioned, we follow this notation except when directly quoting from other sources.

Race

Defining the roots of race has been and continues to be a point of contention. Despite different perspectives, race and racism have pervaded the social and political fabric of the world. Particularly in the United States, racism is at the epicenter of inequalities in income, health, and life outcomes.

Race is a social category constructed by socioeconomic and political forces that determine its content and importance.[1] In other words, race is determined by how society perceives you and you perceive society, which in the United States is largely centered around skin color and other arbitrary markers of difference from “whiteness.”[2] Race exists as a sociopolitical category with origins in oppression. Race has no biological basis.

Biomedical researchers and social scientists have established that the concept of race cannot adequately or accurately describe global human genetic diversity.[3] Populations cannot be distinguished by clear sets of genetic markers, and there is vast genetic variation within each so-called race, with more diversity within populations than between populations. There is vast genetic variation across the entire human species, and relatively little genetic variation between racially defined groups. The traits falsely used to distinguish races do not predict other biological traits.[4]

In medicine and health research, race must be distinguished from ancestry, which refers to a person’s genealogical history.[5] The concept of race is an inadequate proxy for the genetic and cultural variations that can result from differing ancestral origins due to the arbitrary categorization of cultures and people under “race.”[6] The conflation of race with ancestry perpetuates false science and can unintentionally perpetuate racism in biomedicine.[7] Any discussion of ancestry and race in clinical medicine must also acknowledge that ancestry and genetics are just one small piece of the puzzle, which should include the social and structural determinants of health discussed previously. For more on the difference and its use in medicine and research, see Section 3: Race-based Medicine in Diagnosis and Treatment.

Race has no genetic or scientific basis. While there are certainly population differences between groups from around the world, the biological signatures that make up a population do not align with social categories or understandings of race. Throughout this paper, biological racial difference will be used to call out the false idea that there is a natural, biological difference between individuals who identify according to politically and socially constructed categories of race.

It is critical to our vision that medicine disentangles itself from these false ideas of biological difference based on race.

White Supremacy

The construct of race provides the foundation for white supremacy, which is both a political ideology and a racist belief that is woven throughout the foundation of the health systems in the United States. It endorses the superiority of the white race both overtly and in less visible ways. White supremacy maintains and endorses the societal structures wherein white people hold the most power. This can be traced from the beginning of the United States to present day and does not necessarily function in a linear or singular way. Scholar Andrea Smith provides one framework for understanding the mechanisms of white supremacy, wherein it is upheld by three distinct but interrelated logics.[1]

Logic 1: Slavery and Capitalism

The logic (or logical foundation) of slavery values Blackness as nothing more than property and potential profit. Capitalism demands that a laborer’s work becomes a commodity, and those at the bottom of the hierarchy must offer up even their embodied selves as a potential for profit for someone else. This hierarchy is maintained by the logic of slavery. Thus, at the root of anti-Black racism, Black folks’ humanity is denied and valued only by their production capability and exploitative profit. This logic continues in modern day, most notably reflected in the current carceral system.

Logic 2: Genocide and Colonialism

In order for non-Indigenous people to claim ownership and governance over the United States (colonialism), Indigenous people must disappear (genocide). This is enacted both physically—from the historical murder, removal, and segregation of Native Americans to the current systematic disinvestment and breaking of treaties—and with cultural norms that erase Native American peoples and their sovereignty from the collective dominant psyche. This logic was most recently disrupted in recent protests at Mauna Kea and the Dakota Access Pipeline.[2], [3]

Logic 3: Orientalism and War

Throughout history, the West (both the United States and broader colonial powers) defined itself in opposition to the “exotic” and inferior “Orient” (defined more broadly than just Asia). These people thus are defined as inferior and posing a constant foreign threat to the “empire.” This constant implication of war leads to xenophobia and anti-brown racism against Asian Americans, Arabs, Hispanics, and more, justified by the need for strength against the “invading threat.”

These logics are interlocking and reinforcing, but all ultimately ensure that whiteness is privileged and kept in power above all others. White supremacy is at the root of all types of racism outlined below and thus at the core of racist health-care practices and health disparities. We see this in the clinical guidelines and medical texts discussed throughout this paper. White supremacy creates a racial hierarchy throughout the structures of our world and is at the root of the conflation between race and biology in order to establish the “(false) naturalized racial hierarchy” mentioned previously. A key fundamental result in medicine of white supremacy is that people of color are inherently viewed as carriers of disease.

While this paper is designed to be educational, it is by no means exhaustive. We hope that those who are ready to eradicate the harms of the legacy of racism in the field of medicine continue to read both our work and the cited sources, many of which are authored by Black and Indigenous scholars of color who have done tremendous work to bring these conversations to the world (see appendix for further reading).[4]

Racism

Racism is a system of power that upholds the political and social capital of white supremacy in the United States. Racism is deeply embedded in social, political, and economic structures. Most popular perceptions of racism only address the interpersonal prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism based on the belief that certain racial groups are superior to the other. But this only addresses one small part of the ways that racism is embedded in people’s assumptions, institutions, and structures. Thus, racial prejudice, as just one aspect of racism, refers specifically to discriminatory attitudes and actions between people based on the assumption that a particular race is superior or inferior to another, and that a person’s race defines a person’s internal traits.[1] Power refers to authority granted by sociopolitical and economic structures for access to sources, to reinforce racial prejudice.

Racism produces and reproduces social, economic, and political inequalities, and is thus a fundamental cause of disease. Racism is complex and interwoven, and beginning to be studied as a determinant of health and outcomes. But these studies have not been sufficiently incorporated into medical and clinical education, research, and practice.

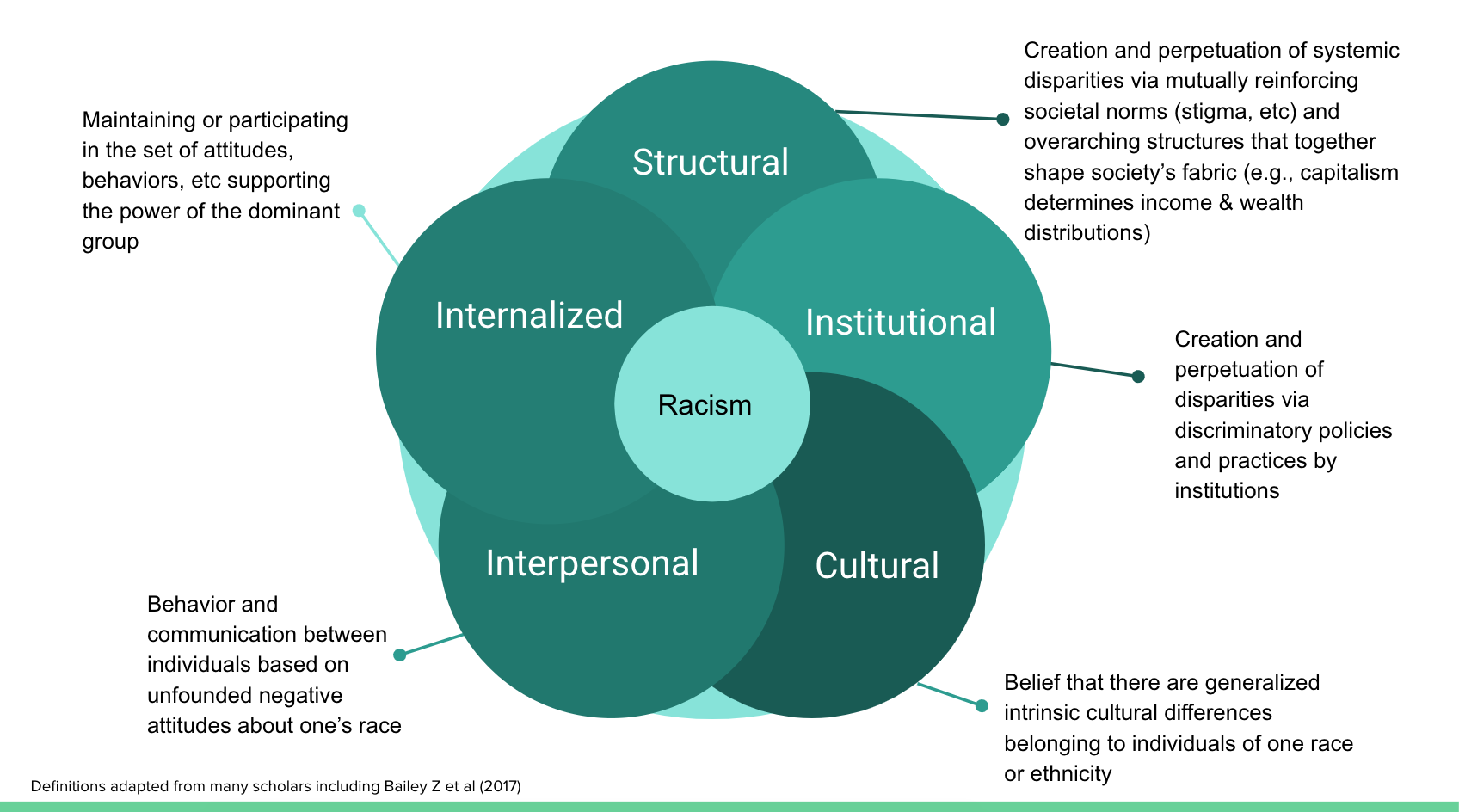

In order to address the many ways racism can shape medicine, we categorize it into internal, interpersonal, cultural, institutional, and structural levels. These levels interact with and work upon each other to reinforce racial hierarchies and can be experienced simultaneously.

Together, these levels make up the society in which we practice.

Although many other disciplines use “systemic racism” to describe the entrenched racially prejudiced power differentials mediated by institutions, we use “structural racism,” as this is the nomenclature we have been taught in public health and medicine. We agree with the Aspen Institute that structural racism tends to include an analysis of the “historical, cultural, and social psychological aspects of our current racialized society,” which we strive to include in our work here.[2] However, for the purposes of interdisciplinary dialogue and learning, we propose they are similar enough to be considered synonyms.[3]

The following examples demonstrate how racism functions on various levels to create, perpetuate, or exacerbate health disparities, although it is nowhere near exhaustive.

Image by Maddy Kane

Interpersonal Racism

Definition: Interpersonal racism is behavior and communication between individuals based on unfounded negative attitudes about one’s race or culture. There is a wide spectrum of interactions that can occur under the category of interpersonal racism from explicit direct violence to “implicit” microaggressions, all of which have negative consequences on health outcomes.

Interpersonal racism is often understood as the “classic example” of racism—the harassment and violence associated with the civil rights movement, Jim Crow, and other points in history. It’s important to acknowledge that although strides have been made, interpersonal racism includes all-too-common microaggressions and that interpersonal racism is just one of many interlocking forms of racism that medicine must address.

In medicine, interpersonal racism affects both providers and patients of color. One current issue is the racial microaggressions in the clinical learning and care environment, which have consequences beyond the “micro,” such that these negative interactions falter trust between patients of color and health-care providers.[1] Defined as “the everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults, whether intentional or unintentional,” microaggressions can be found in everyday conversations and encountered in any social setting.[2] These range from being assumed to be a criminal, being presumed to be inferior, being exoticized, or being treated as a second-class citizen. Examples of microaggressions in a clinical learning environment include telling high-achieving students of racial or ethnic backgrounds that they are “smart for a [insert ethnicity] person,” expecting an individual of any particular group to “represent” the perspectives of others of their race, and singling individuals out because of their backgrounds. These can alienate learners, exacerbating imposter syndrome and dropout rates, as well as directly affecting health.[3]

Direct health consequences of microaggressions include greater perceived stress, depressive symptoms and negative affect, and physical health issues such as increased history of heart attack, pain, and fatigue.[4] These experiences of discrimination for trainees and patients have been associated with elevated blood pressure, breast cancer, low birth weight, lower back pain, and more.[5]

Finally, while microaggressions can be perceived as harmless, such racial stereotypes can ultimately become matters of life or death. The deaths of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown are a result of interpersonal racism colliding with structural factors: the negative racial stereotypes assuming Black boys are criminals alongside policies that allow for and encourage unnecessary lethal force results in continued tragic killings and the ongoing threat of violence to the community.[6]

In the field of medicine, attempts to address interpersonal racism have focused almost exclusively on implicit bias. Implicit bias is a psychological concept that embedded stereotypes affect decision-making without conscious thought, which is often interpreted as an individual problem when in fact it stems from and resonates with structural oppression. In health care, this leads to poor interpersonal and systemic outcomes, such as lower empathy, higher distrust, and lower referral rates for specialty care.[7] Yet most trainings do not grapple with racism in its entirety and let providers “off the hook” for owning and addressing the effects of racism in health care. Implicit bias work doesn’t usually address the structural and systemic forcible exclusion or pathologization of brown and Black bodies. Many implicit bias trainings get hung up on “intention” and the assumption that these biases are unintentional, which allows providers to continue to think of themselves as fundamentally good people. But the narrow focus misses the multitude of ways racism functions in medicine and doesn’t create a way for health-care providers to see and address our complicity in these systemic harms (which function whether or not we have good intentions as individuals). Furthermore, rather than a paradigmatic shift like that of cultural humility (over its predecessor, cultural competency), implicit bias is often seen as yet another training, a knowledge to be acquired in isolation from the historical and multifaceted context of racism.

Rather than a reliance on individual knowledge, we encourage the practice of self-interrogation of potential micro- and macroaggressions in the medical field. This not only will encourage ongoing reflection but likely will require providers to acknowledge and address more systemic and structural factors.

Internalized Racism

Definition: Internalized racism occurs when “a racial group oppressed by racism supports the supremacy and dominance of the dominating group by maintaining or participating in the set of attitudes, behaviors, social structures and ideologies that undergird the dominating group’s power” [1]. Internalized racism is a product of internalized colonialism, in which non-white colonized people begin to uphold the values and social signifiers of white colonizers and lose identities.

Internalized racism has significant mental and physical health consequences, including negative self-esteem, a sense of inferiority or victimhood, ethnic self-hatred or self-doubt, and navigating the additional emotional burden of overcoming racialized or stereotype-driven interactions.[1] In addition, internalized racism contributes to the perpetuation of negative racial stereotypes not only by dominant cultures (e.g., white people), but also within racial groups themselves.[2]

With regards to physical health, a long-standing and widespread social phenomenon that is a consequence of internalized racism can be seen in the practice of skin whitening among immigrants from, and individuals living in, formerly colonized places such as the Philippines, India, and Nigeria.[3] Finally, emerging research suggests that internalized racism has effects on body mass distribution and insulin resistance.[4]

Potential remediation of internalized racism includes increasing awareness; reframing racism away from the individual (adopting a systemic and structural understanding aimed at liberation from oppression); increased training for providers, researchers, journalists, and others to recognize internalized racism as well as stop perpetuating potentially harmful interactions; and providing opportunities for in-group healing dialogues.[5] The field of medicine can begin to address internalized racism by increasing awareness across providers, affirming patients’ strengths and humanity, and incorporating antiracist policies and practices across systems.

Cultural Racism

Definition: Cultural racism occurs through belief that there are generalized intrinsic cultural differences belonging to individuals of one race or ethnicity. It is important to note that race and ethnicity are social categories. While individuals within racial and ethnic groups may have similarities, cultural racism arises in the assumption that everyone in one racial/ethnic group has the same cultural values, habits, and beliefs.

Medicine has a history of aligning cultural generalizations and “behaviors” with risk factors of disease, which perpetuates cultural racism. This practice has shaped clinical practice and research on health disparities by reducing complicated phenomena to broad and oversimplified assumptions of characteristics and behaviors.

Contemporary research in health disparities oftentimes provides the “scientific” basis for clinical overgeneralizations by framing racial groups in ways that perpetuate cultural racism. Perhaps the most overused heuristic is that of diet and nutrition: certain racial and cultural groups are generally assumed to subscribe to a poor diet by “cultural preference” and thus prone to higher rates of certain diseases like diabetes and hypertension.[1] Focusing on cultural aspects and individual behavior as sole determinants of racial health disparities is misleading, ignores structural factors that perpetuate disease, and tends to perpetuate notions of racial inferiority and negative stereotyping.

Research also feeds into clinical practice. The 1992 University of California, San Francisco, (UCSF) Nursing Cultural Competency manual organized subsections on common characteristics, habits, and beliefs by race and culture. Mexican patients were characterized as oftentimes “dirty,” having “cultural values that do not believe in regular daily cleansing.” A 1996 publication, Culture and nursing care: A pocket guide, divides care into chapters such as “Gypsies,” “Haitians,” “Japanese Americans,” “Black African Americans,” “South Asians,” and more.[2] A presumably “updated” yet similarly divided book published by UCSF Nursing Press by the same authors (Lipson and Dibble) in 2005 states, “Haitians tend to avoid eye contact, are not concerned about sharing personal space with others, and exhibit low threshold of pain.”[3] Despite its intent to provide tailored care to diverse patients, cultural competency ultimately operates by relying on assumptions that overgeneralize specific cultural values to all people of a certain race or ethnicity.[4] The stereotypes and coarse categorizations of cultural competence in the UCSF Nursing Press books above continue to be cited in more current and progressive-seeming nursing texts, such as Community/Public Health Nursing Practice and Public Health Nursing: Population-Centered Health Care in the Community.[5] Cultural competency, still taught and practiced in many institutions today, can thus be seen as a form of cultural racism.

Rather than perpetuating cultural racism and cultural competency in education, research, and practice, new movements in incorporating cultural humility in health-care settings have allowed for self-reflection and lifelong learning.[6] Rather than notions of achieving complete “knowledge” and “awareness” of knowing certain cultures, cultural humility centers push for a critical lens to power dynamics as well as learning with and from clients about the cultural values and beliefs they uniquely hold as individuals.

Institutional Racism

Definition: State and nonstate institutions, such as government, education, and health care, create and perpetuate “racially adverse discriminatory policies and practices” disparities in social and structural determinants of health by controlling where people of color can live, learn, work, and play.[1] [2]

Medical institutions have both participated in segregation and actively inflicted race-based harm on communities. Two of the most stark examples are the forced sterilization and obstetrics experimentation on womxn of color. From the earliest times of slavery to present day, American society has overtly and subtly tried to control the reproductive capacity of Black women. This has ranged from overt (e.g., forced sterilization, experimentation of new OB-GYN surgeries on slave women, testing the invention of birth control) to more subtle ways (e.g., characterization of Black mothers as both “incurably immoral” and “hyperfertile”).[3]

Today, Black women are three to four times more likely to experience a pregnancy-related death than white women.[4] This maternal mortality crisis is rooted in institutional and structural racism both within and external to the health-care system.

Several medical organizations have issued policy statements about racism and its effects on health. For example, in 2018, the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine (SAHM) issued a policy paper titled “Racism and Its Harmful Effects on Nondominant Racial–Ethnic Youth and Youth-Serving Providers: A Call to Action for Organizational Change.” The recommendations issued by these, and other, medical organizations are vital steps toward antiracism in medicine. As the SAHM paper states, “Organizations involved in clinical care delivery and health professions training and education must recognize the deleterious effects of racism on health and well-being, take strong positions against discriminatory policies, practices, and events, and take action to promote safe and affirming environments.”[5]

Furthermore, medical institutions must eradicate the racism currently embedded in everyday clinical guidelines and practice such as those that lead to the current maternal mortality crisis. Institutional policies that disproportionately push women of color to have unnecessary C-sections at far higher rates than their white peers, reduce access to prenatal and postnatal care, and lead to higher rates of untreated chronic conditions are examples of institutional racism leading to disturbing disparities in maternal mortality.[6]

Structural Racism

Definition: Zinzi Bailey et al. (2017) define the difference between institutional and structural racism as follows: “Structural racism refers to ‘the totality of ways in which societies foster [racial] discrimination, via mutually reinforcing [inequitable] systems…(e.g., in housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, credit, media, health care, criminal justice, etc) that in turn reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources,’ reflected in history, culture, and interconnected institutions” (emphasis added).[1]

These interlocking systems interact to create societal norms or beliefs and create the institutional policies and laws that lead to institutional determinants of health. These overarching structures are called structural determinants of health. Structural determinants of health, including structural racism, build the many facets of the unequal social and physical environment in which we live. Structural racism could therefore be called a “fundamental cause” of health disparities.[2] The interlocking systems explain the unrelenting and unequal impact of past policies and laws, which have entrenched inequities by entrenching unequal access across many systems, and continue to reverberate in today’s policies, practices, and laws (today’s institutional racism). To address health disparities without addressing fundamental causes like structural racism is incomplete and inaccurate, and much of the science we critique in this paper lacks that view.

As Bailey et al. note, structural racism begins with the categorization of Black, brown, and Indigenous bodies, creating systems of oppression that are both explicit and hidden from view, as well as propagating violence, even genocide. In today’s world, structural racism affects where someone can live, through past restrictive housing laws and loan availability, whether or not they will be arrested and jailed for minor drug offenses, through the War on Drugs, and many other systems. The interlocking effect has been an “entrenchment of racial economic inequities” as well as exclusion from resources and institutions that promote health and well-being.[3] Structural racism ensures that cost, access (financial, geographical, material), language, community influence, and stigma can limit and negatively affect one’s ability to freely access these institutions.

One example of the interlocking systems of structural racism is the exclusion of Black people from housing and employment. After Jim Crow segregation ended, Black people were excluded from the Social Security Act by excluding agricultural and domestic workers (at the time, jobs largely held by Black people) and excluded from the benefits of policies like the GI Bill by de facto exclusion from housing. At the colleges that would accept returning Black war veterans, there was no nearby housing that would be sold to Black people due to practices such as redlining, which structured who could get mortgages after the Great Depression based on the “desirability” of neighborhoods. That desirability score included an assessment of how many Black, immigrant, and other “undesirable” people lived there. Although redlining is no longer legal, its effects continue. One recent study shows that asthma rates continue to be higher in formerly redlined neighborhoods than their surrounding neighborhoods.[4] Black families were systematically excluded from wealth creation.

Furthermore, the criminal justice system interlocks with housing and employment to continue the lack of access to housing and employment. The War on Drugs and “tough on crime” policies increased the visibility of this intersection and continue to disproportionately affect Black and brown communities, both through disproportionate incarceration (for the same crimes as white people) and the social, economic, and psychological consequences of incarcerating so many Black and brown people. These interlocking systems continue to affect the health and well-being of individuals and communities through direct and indirect health effects. Bailey et al. report increased levels of myocardial infarctions, low birth weight pregnancies, and psychological stress, both chronic and acute, among many other adverse outcomes.[5]

These zoning laws and their consequences also create environmental racism, in which predominantly Indigenous, Black, and Latinx people are zoned into areas with environmental hazards ranging from damaging air pollution, to Superfund sites near their homes, to disproportionate burdens of climate changes. These communities are thus overexposed to environmental hazards and bear a disproportionate burden of respiratory and skin diseases, as well as increased epigenetic changes that can later affect their health.[6]

Why does all this matter?

As medical students, we believe it is crucial to our understanding of the health and well-being of our patients and ourselves, of our society, to know these levels of racism. We must know how they work, how they have worked, and how they will continue to work. Research has begun to scratch the surface of the many ways this plays out in patients’ and providers’ lives, but we must reshape the way we understand and practice medicine and health to include a frank look at the history of the United States’ treatment of Black and brown people, and its consequences for today.

In a society where race has been a normalized part of everyday life, medicine must acknowledge that use of race as a risk factor or predictor of health outcomes is simply false science. Because of its significance in shaping political discourse and social relations in the United States, race has become a social construct and political identity. An individual’s racial identification has real economic and psychosocial consequences on lives, becoming a central influence in US history resulting in unequal outcomes across various life outcome indicators, including income, wealth, health, birth and mortality, and more.

As such, racism, not race, is a key determinant of health. Racism—the discrimination according to one’s racial category—has become an arbiter of health disparities and dismal life outcomes in the United States.

Thus, medicine must come to terms with the two truths:

(1) Race has no biological basis.

(2) Racism has been and continues to be a key determinant of disparate health outcomes, especially in the United States.

Once we acknowledge the role of all the levels of racism, we can build a better way. Clinics must continue to advocate for policies and laws that address both structural and institutional racism. Researchers must take structural racism into account, no matter their field of study, and begin to study the effects of racism directly. Educators must teach this legacy, and clinicians must know how it affects their patients and their peers. We have to broaden the conversation in medicine and health to include institutional and structural racism alongside the other types in order to create a truly antiracist, just, and healing medical system.